Why Do People Obey?

What the Stanley Milgram Experiments Reveal About Power, Authoritarianism, the Death of Renee Nicole Good, and the Road to Democratic Revolution

Earlier this week, as part of The Revolution Will Be Televised series I’ve been writing on Substack, I created and posted a short video about the killing of Renee Nicole Good, set to Buffalo Springfield’s classic song, For What It’s Worth.

The song felt right—not because it explains anything, but because it captures a familiar unease: the sense that something is horribly wrong.

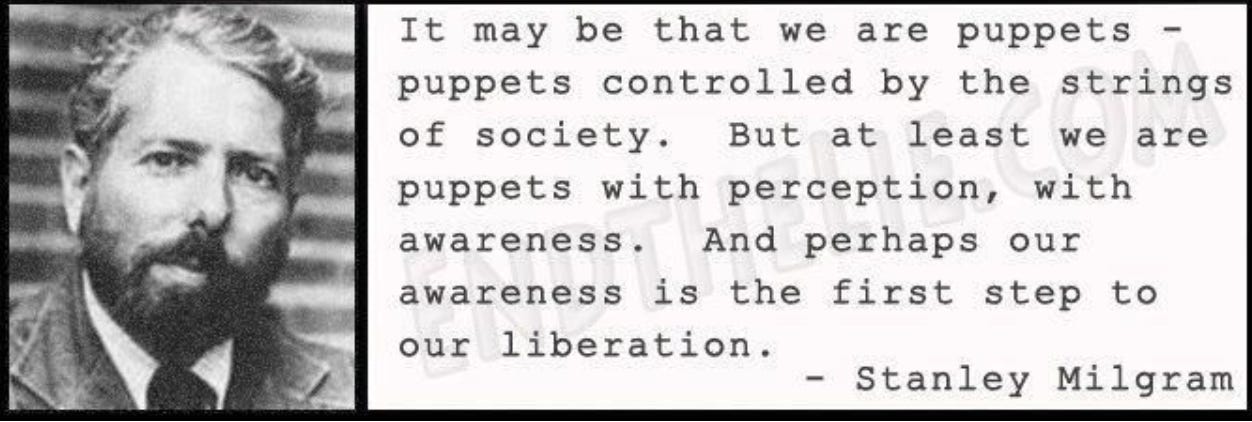

This essay picks up from that feeling and moves deeper. It looks at Stanley Milgram’s experiments on obedience to authority—and why they remain painfully relevant today, in a world where violence often emerges not from chaos, but from compliance and obedience to authority.

This essay also ties into the essays I wrote about the late Gene Sharp, who was the world’s leading expert on nonviolent revolution. As I wrote, Gene Sharp treated nonviolence as a science, and had two core questions that drove his work: Why do people obey?; and How could they stop obeying, nonviolently?

His core insight was this:

Political power depends on human obedience. Withdraw that obedience, and even the strongest regimes collapse.

The Death of Renee Nicole Good

Renee Nicole Good was killed during the exercise of state power, murdered by an ICE agent. Not in a war. Not in a riot. Not in a moment of collective breakdown. But in the space where authority expects to operate smoothly and without question.

An ICE agent fired the shots. Contradictory statements followed. An investigation was announced. The language of legitimacy settled in quickly, doing what it is designed to do: absorbing the shock, containing the disruption, restoring order.

And yet, something isn’t right.

Because when a life is taken in the name of policy—when lethal force emerges not from chaos but from compliance—we are no longer looking at an isolated tragedy. We are looking at a pattern. One that asks us to slow down, look around, and ask what kind of system produces moments like this—and why so many people inside that system experience them as simply “doing the job.”

That question is not new. It has been with us for decades, especially during the era of Nazi Germany.

This question was brought into sharp, unsettling focus by a psychologist who wanted to understand how obedience itself could become dangerous.

The Experiment

In the early 1960s, a young psychologist at Yale, Stanley Milgram, set out to understand how the Holocaust had been possible, in his experiment “Obedience to Authority.” Not whether the Nazis were uniquely evil, but how so many ordinary people—teachers, clerks, engineers—had participated in a system of mass violence.

Milgram, a Jew, was grappling with a moral puzzle that the world had not yet fully processed: the Holocaust. He wanted to understand: how could ordinary people participate in atrocities? Were Germans uniquely obedient?

Or was obedience an element of human psychology that could surface anywhere under the right conditions?

He wanted to know: is it possible that good people will obey harmful orders, simply because an authority figure tells them to?

Milgram’s experiment was deceptively simple. Volunteers were instructed to administer electric shocks to another person whenever that person answered a question incorrectly. The shocks increased in intensity, eventually labeled with warnings like “Severe Shock” and “Danger: Extreme Shock.” Unknown to the participants, the shocks were fake, and the person receiving them was an actor.

What mattered was not the apparatus, but the authority overseeing it.

A man in a lab coat holding a clipboard stood nearby, calm and professional. When participants hesitated, he reassured them: “The experiment requires that you continue.” No threats. No anger. Just certainty.

A majority of participants continued administering shocks even as they believed the person on the other end was screaming in pain, begging to stop, or possibly unconscious.

They did not do so because they were sadists. They did so because responsibility had been displaced.

Gene Sharp taught us how obedience functions in political systems. Stanley Milgram showed us why people obey in the first place.

Obedience Without Hatred

Milgram’s most unsettling finding was not that people enjoy inflicting harm. It was that people will inflict harm without hatred, without malice, and often with visible discomfort, so long as authority assures them the responsibility is not theirs.

Participants frequently protested. They expressed anxiety. Some laughed nervously or trembled. But when told they were not personally accountable—when the authority figure framed the act as necessary, procedural, scientific—they continued.

Milgram called this the agentic state: a psychological condition in which individuals no longer see themselves as moral actors, but as instruments executing another’s will.

Conscience does not disappear in this state. It is overridden.

Milgram concluded from his experiment that obedience to authority was not limited to any nation, culture, or personality type. It was deeply human.

This single insight becomes a profound lens for understanding the rise of authoritarian movements, the erosion of democratic norms, and even the political landscape of the United States today.

From Lab Coats to Badges

It is tempting to see Milgram’s experiment as a relic of the past—a Cold War curiosity we reassure ourselves could never be repeated. But the experiment was never really about electricity: it was about legitimacy.

The lab coat signaled expertise.

The clipboard signaled procedure.

The institutional setting signaled that someone else had already decided what was right.

Now, fast forward to today: replace the lab coat with a badge; replace the experiment with policy; and replace the shock generator with a firearm.

The psychological structure remains.

When authority is normalized, when harm is routinized, when language turns people into categories—targets, enforcement actions, removals—violence no longer feels like a moral choice. It feels like compliance.

This is how obedience becomes lethal without ever feeling personal.

Indiscriminate Harm as a System Outcome

The killing of Renee Nicole Good was not the result of an ICE agent waking up intending to take a life. That assumption—comforting as it may be—misses the deeper danger.

Stanley Milgram showed that systems do not require cruelty to function violently. They require only procedures that disconnect action from consequence.

In his experiment, participants could not assess proportionality. They could not see the full context. They were not asked to weigh outcomes. They were told the process had already been designed and approved.

In modern enforcement regimes, the same logic applies. Individuals become abstractions. Context collapses. Force becomes standardized. Tragedy becomes incidental.

This is not a failure of character. It is a failure of moral design.

The Banality of Obedience

Hannah Arendt famously described the “banality of evil” in her reporting on the 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann, the Nazi official who was one of the main organizers of the Holocaust. Milgram provided its psychological mechanism.

Evil, in this sense, does not arrive roaring with rage. It arrives quietly, wrapped in protocol, delivered by people who believe they are simply doing what is required of them.

That is what makes obedience so dangerous: it does not ask whether an order is just. It asks whether it is authorized.

From Obedience to Withdrawal

Renee Nicole Good’s death should not be understood as a freak occurrence, nor as a problem that can be solved solely with better training or clearer rules of engagement.

It should be understood as a warning.

Stanley Milgram showed us that the greatest danger does not come from monsters, but from ordinary people who have learned to hand their moral judgment upward—to institutions, procedures, and authorities that claim legitimacy. When responsibility is displaced, violence does not feel like violence. It feels like compliance.

This is why obedience sits at the center of every authoritarian system—and why it is also the system’s greatest vulnerability.

As Gene Sharp argued, power is never sustained by force alone. It depends on the cooperation of those who carry out orders, enforce rules, and normalize harm. When that cooperation is withdrawn—when people refuse to participate in injustice—the system falters.

Stanley Milgram taught us how obedience is manufactured. Gene Sharp taught us how it can be undone.

The question before us, then, is not whether obedience can go too far. History has already answered that. The question is whether we recognize the moment when obedience must give way to conscience—and whether we are willing to act on that recognition before the next life is absorbed into procedure.

And the most important choice is whether we continue to follow along—or decide to stop.

Coda

I wrote this essay as a necessary sequel to the short video I created and posted a few days ago, Renee Nicole Good: For What It’s Worth. The song For What It’s Worth has always carried the feeling of a warning half-heard—something unfolding in plain sight while people hesitate to name it.

The video doesn’t explain what happened to Renee Nicole Good. It doesn’t need to.

It sits with the discomfort. It lingers in the space where authority asserts itself, where violence arrives quickly, and where the question is not yet, What do we do? but Do we see it?

This essay begins where the video leaves off: with the recognition that obedience is not neutral—and that what feels procedural can be deadly.

This exploration of Milgram's experiments in the context of modern authoritarianism is absolutley powerful! The connection between the agentic state and systemic violence, where people become instruments executing orders without personal responsability, is exactly what we need to understand about obedience to authority today. Sending good vibes!

I believe that we experience stages of cognitive development and stages of moral development. Unfortunately, moral development is harder to achieve. We often get stuck in a law and order stage and fail to develop more altruistic, see holistic and inclusive level of seeing the good outside our own tribe and our responsibility for making honorable choices.