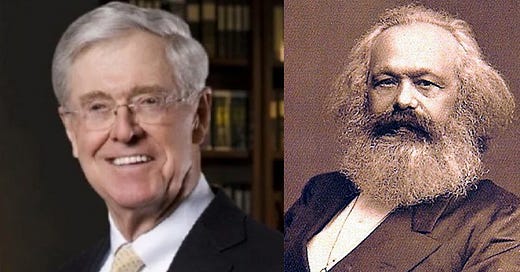

What Do Charles Koch and Karl Marx Have In Common?

They Actually See Eye to Eye on Something Very Important

Do Charles Koch and Karl Marx really have anything in common? Before your head explodes just pondering this question, let’s explore this a little more by way of introduction.

Charles Koch is one of the richest men on the planet, with a net worth of over $50 billion. His company, Koch Industries, is the largest privately held company in the U.S., with revenues of $115 billion—greater than Facebook, Goldman Sachs, and U.S. Steel combined. Koch Industries is also one of the biggest industrial polluters and emitters of toxic wastes in the world.

Politically, he is a libertarian, believing in the power of free markets and also the imperative of a limited government, in which free enterprise can replace many functions currently provided by government entities; his belief is that the only purpose of government should be to protect private property.

He is also well known for having created the Koch Network, a far reaching and far ranging network of right wing billionaires, who by virtue of their money have molded government to fit their libertarian ideologies, subsidized climate denial organizations, sponsored think tanks and university centers to promote their strident beliefs, and pushed a corporate friendly agenda into the overall zeitgeist.

Jane Mayer, the New Yorker investigative journalist and author of the deeply researched and profoundly insightful book, Dark Money: The Hidden History of the Billionaires Behind the Rise of the Radical Right, details in the book the history of the Koch family, how they got their money and what they do with it, and the deleterious imprint they have left on the world.

Karl Marx, on the other hand, is the infamous writer, philosopher, journalist, social critic, and revolutionary who was prolific in his literary output, with his most famous titles being the pamphlet The Communist Manifesto and his three volume Das Kapital.

Considered one of the principal architects of modern social science, Marx’s main themes in his writings were class struggle and the dissection of who should own the means of production, as related to labor and capital.

Marx has inspired socialists and Koch has inspired capitalists—the chasm between the two is a mile wide and a mile deep.

What could they ever have in common?

Is it a connection to Germany? Marx was German, while the American Fred Koch, Charles’ father and the founder of Koch Industries, made his fortune in Germany, building oil refineries for Hitler.

Nope, that’s not it.

Is it a love of Republicans? Charles is a dyed-in-the-wool libertarian Republican, while Marx was friends with and influenced the first Republican president, Abraham Lincoln.

Nope, that’s not it.

Is it a love of democracy? Karl Marx thought very highly of democracy, while Charles Koch has done his best to corrupt and destroy democracy.

So nope again, that’s not it.

Then what could they ever have in common?

It’s this: a devotion to the liberation of the individual, by way of human flourishing—best known in modern times as self-actualization, a concept originated by the psychologist Abraham Maslow, whose pioneering work in self-actualization inspired the human potential movement. Self-actualization is the highest level of psychological development, and where personal potential is fully realized.

Obviously, since Maslow was born in 1908 and Marx died in 1883, Marx didn’t know anything about self-actualization, but his ideas are aligned with it.

Both Marx and Koch were learned men and voluminous readers, with similar influences: the Greek philosophers Aristotle and Epicurus, and the Enlightenment thinkers Adam Smith, John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and David Hume, among others.

Besides these commonalities in influences, Marx was also influenced by Shakespeare, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Georg Hegel, Charles Dickens, Goethe, and the American Revolutionaries Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine.

Koch is also influenced by the Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek, who is the founder of neoliberalism; Viktor Frankl, the Holocaust survivor whose book about his concentration camp experiences, Man’s Search for Meaning, was an international bestseller; Frederick Douglass, the great American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman, who after escaping from slavery went on to write and speak incisively against slavery and for equality for all peoples; and the iconic Bob Dylan.

Charles’ belief in libertarianism is deeply intertwined with his interests in self-actualization. He believes that when people are freed from government rules and regulations, then, as it says on the mission statement of Americans for Prosperity, Charles’ political organization, “people are capable of achieving extraordinary things, when they have the freedom and opportunity to do so…We believe that every person has unique gifts that enable them to realize their American dream.”

And all it takes to do so, in Charles’ telling, is government getting out of the way.

Here’s the talk that Charles gives to interns at Koch Industries:

My advice is to be the best “you” you can be. Don’t try to be something you’re not. Don’t go after shiny objects; find something that fits your gifts and your nature. Because, as Abraham Maslow said, “What you can be, you must be.” If you evade your capacities and your potential, you will be unhappy the rest of your life. You have to believe in yourself and the journey to have a fulfilling life…Self-actualization is to create, on a personal basis, your own virtuous cycles of mutual benefit. Become a lifelong learner. This never ends. If you stop, I quote a Bob Dylan song: Those who “ain’t busy being born are busy dying.” What you want to do is help people find something they’re passionate about, look forward to, and are pumped up about. This keeps them “alive” and contributing. If we had a whole society of this, think what it would be like if everybody is helping others in a way that’s rewarding to them. What a wonderful world we’d have.

You might say that sounds all peace, love, and granola. There is a touch of idealism in this belief system—that humans, left to their own devices, can thrive to their greatest aspirations.

Karl Marx would think highly of Koch’s speech to interns, as he was congruent with Koch’s ideas. Although Marx’s ideas of socialism are most associated with the former Soviet Union and Communist China, they are far from the ideal of what Marx advocated.

Marx never felt socialism could succeed in a feudal nation; he wrote that a feudal nation that embraced socialism would eventually descend into totalitarianism—which is what took place in the Soviet Union under Stalin, and also has taken place in China.

Marx thought highly of democracy, and admired the achievements of capitalism. He saw these achievements as an opposition to political tyranny, universal prosperity, respect for the individual, civil liberties, democratic rights, and an international community.

He just felt that sooner or later, capitalism would implode under its own misdealings, and in the process, destroy democracy. It was then that Marx felt the citizens of a capitalist nation would begin to advocate for a system of socialism, once they realized the limitations of capitalism.

In Marx’s writings, the idea of human flourishing runs deep. Marx wrote consistently about workers owning the means of production, but his view of production is not production at all in the literal sense. He felt that men and women only genuinely produce when they are free to do so, and to do so for their own sake.

Marx believed the best things in life are done just for the hell of it, and that true wealth was, as he wrote, “the absolute working out of human creative potentialities, that is, the development of all human powers as an end it itself, not as measured on a predetermined yardstick.”

And even though Marx talked about workers owning the means of production, the word “production” to Marx covered any self-fulfilling activity: playing the flute, savoring a peach, dancing, engaging in politics, planting a garden, playing baseball, organizing a birthday party for one’s children, and so on.

The key word for Marx was leisure, that people should work less and have more leisure time—and this would happen more than not when workers had more control of their lives.

The big difference between Charles Koch’s version of self-actualization and Karl Marx’s boils down to Abraham Maslow’s dictum as to how a person achieves self-actualization.

Maslow mapped out what he called the Hierarchy of Needs, that when a person had their basic needs met—they were secure financially, had a job, had enough food, shelter and clothing, felt safe and loved—it was then that they could pursue the path of self-actualization, that of achieving a more fulfilled life, full of creativity, love, spontaneity, happiness, enlightenment, and more.

Karl Marx’s vision was self-actualization for the masses—if a society, through its responsibility to its citizens, could provide enough to meet the basic needs of potentially every person (in Marx’s worldview, this should be the prime directive of society), then every citizen would have the capacity to self-actualize.

One of Marx’s most famous sayings is “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs”—in other words, each person’s basic needs should be met. And when the basic needs of the citizenry are met, you then have a more egalitarian society, and a more prosperous society for potentially everyone.

In this type of society, social cohesion runs strong. And hence the word socialism—social, as in social cohesion, is the key part of the word.

In Charles Koch’s vision of self-actualization, it can only be self-actualization for a select few. In a society such as the U.S., where rugged individualism and a cutthroat version of capitalism is the prevailing narrative, you are not guaranteed that your basic needs will be met—you have to earn it, unless you are fortunate enough to be born into the right family, one in which your basic needs are met right from birth.

In a society such as the U.S., in which 80% of people are living paycheck to paycheck, where many people work two and three jobs to make ends meet, and where homelessness is a problem of epidemic proportions, there is no time to achieve self-actualization. For the great majority of Americans, self-actualization is a luxury they don’t have the time to pursue, or the ability to afford.

And therein lies the rub: people truly prosper—physically, mentally, and spiritually—when they are free to self-actualize, when they have the time to pursue the activities that they feel passionate about and that get their creative juices flowing. But if they don’t have the opportunity to go after self-actualization, they suffer—they feel stuck, like a hamster in a cage, just spinning the wheels while going nowhere.

It’s a very liberating phenomena to be free to be who you want to be—both Charles Koch and Karl Marx would agree. But in Koch’s worldview, only a select few can achieve this, while for Marx, this was the primary drive for society—for every person, not just the lucky few.

What would a society look like that allowed for the potential self-actualization of every person? This was the dream of Karl Marx, and it’s the dream of every democratic socialist in the world.

Marx felt a democratic socialist society could permit everyone to have their basic needs met, which would then allow them to attain self-actualization. It’s a vision that has seen some success in the Nordic countries—Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Norway, and Iceland—along with some other developed nations.

These countries aren’t perfect, and they’re more social democracies than democratic socialist states, but they do allow their citizens the freedom to live a life of self-actualization—by virtue of having a strong social safety net—much more so than what takes place in the U.S.

The proof is in the pudding: the World Happiness Report, published every year by the U.N.’s Sustainable Development Solutions Network, consistently ranks the Nordic countries and other social democracies as the world’s happiest nations, while the U.S. has ranked 18th for many years in a row.

That’s the long and short of what Charles Koch and Karl Marx have in common: self-actualization, the liberation of humans. Yet they differ in their philosophy of how it can be achieved.

I think most, if not all of us, would vote for Karl Marx’s version of it—that of self-actualization for everyone. It sure would make for a much more peaceful, loving, and just world.

But right now we live in Charles Koch’s version of self-actualization—and the world ain’t doing so hot these days because of it, y’know?